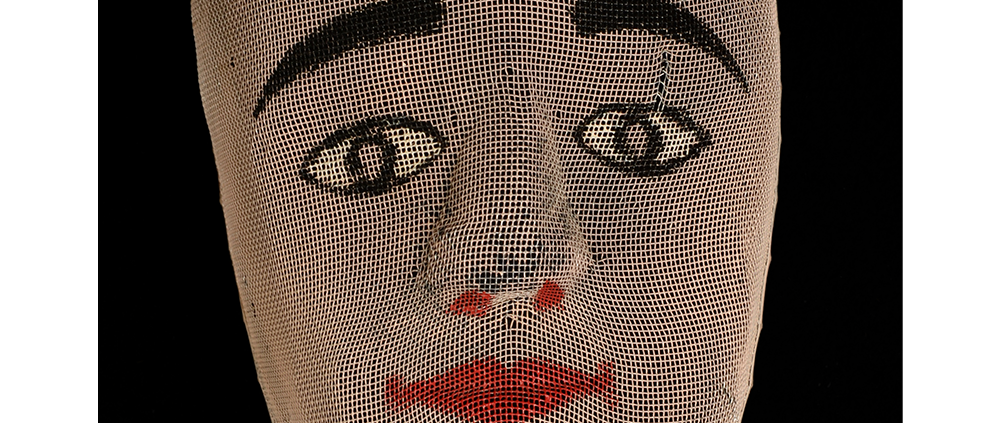

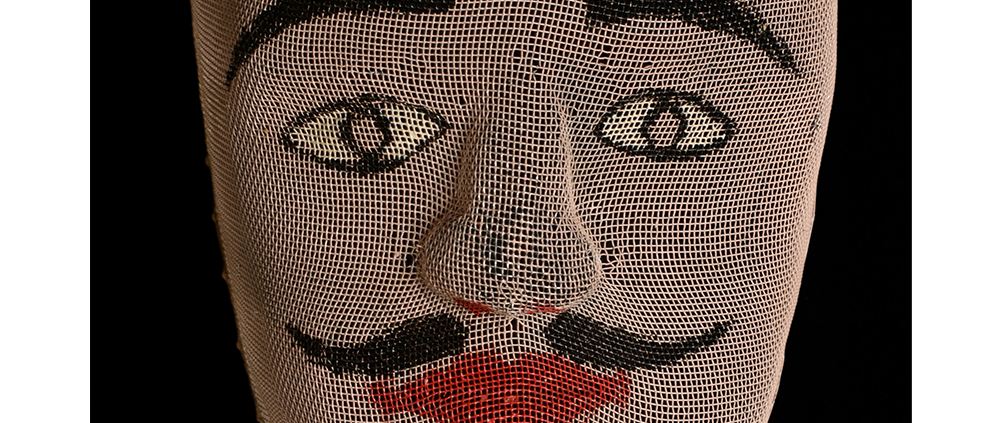

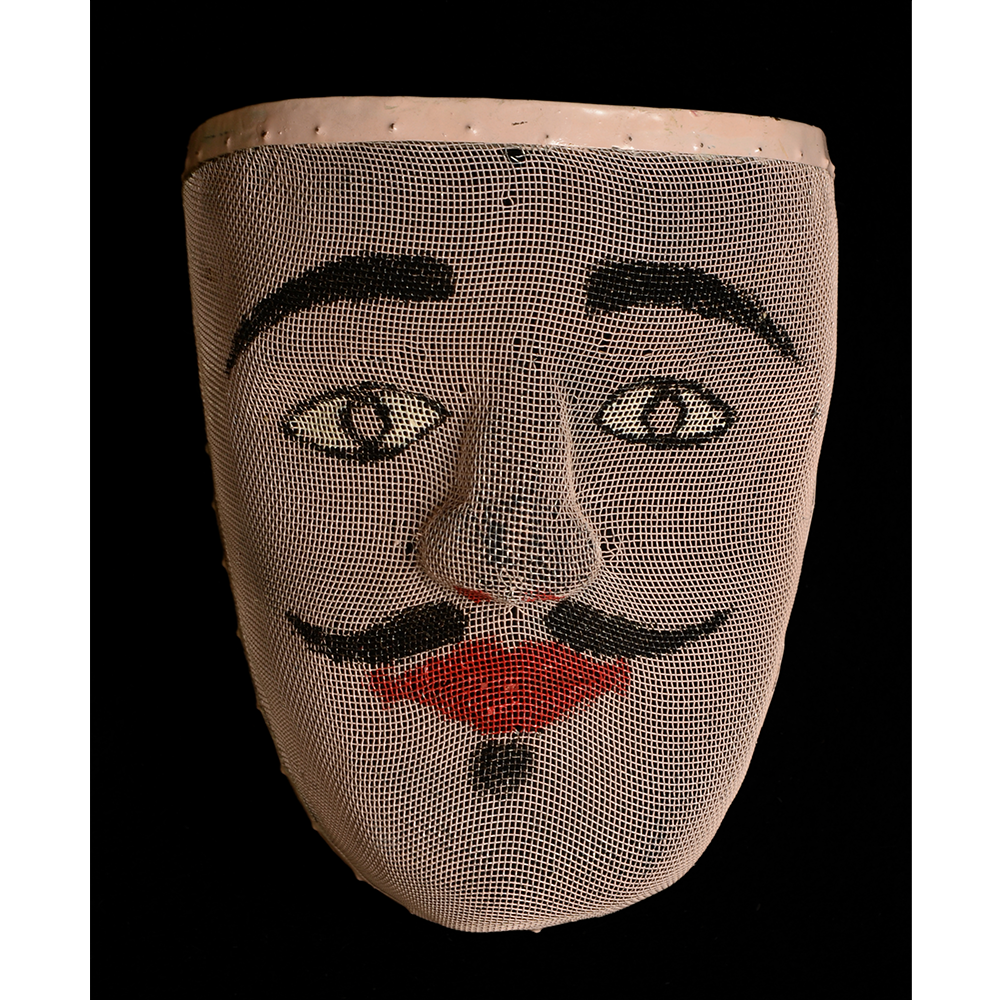

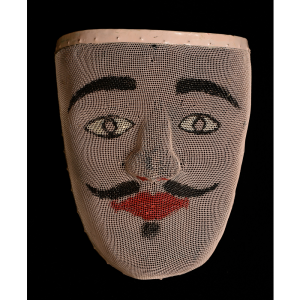

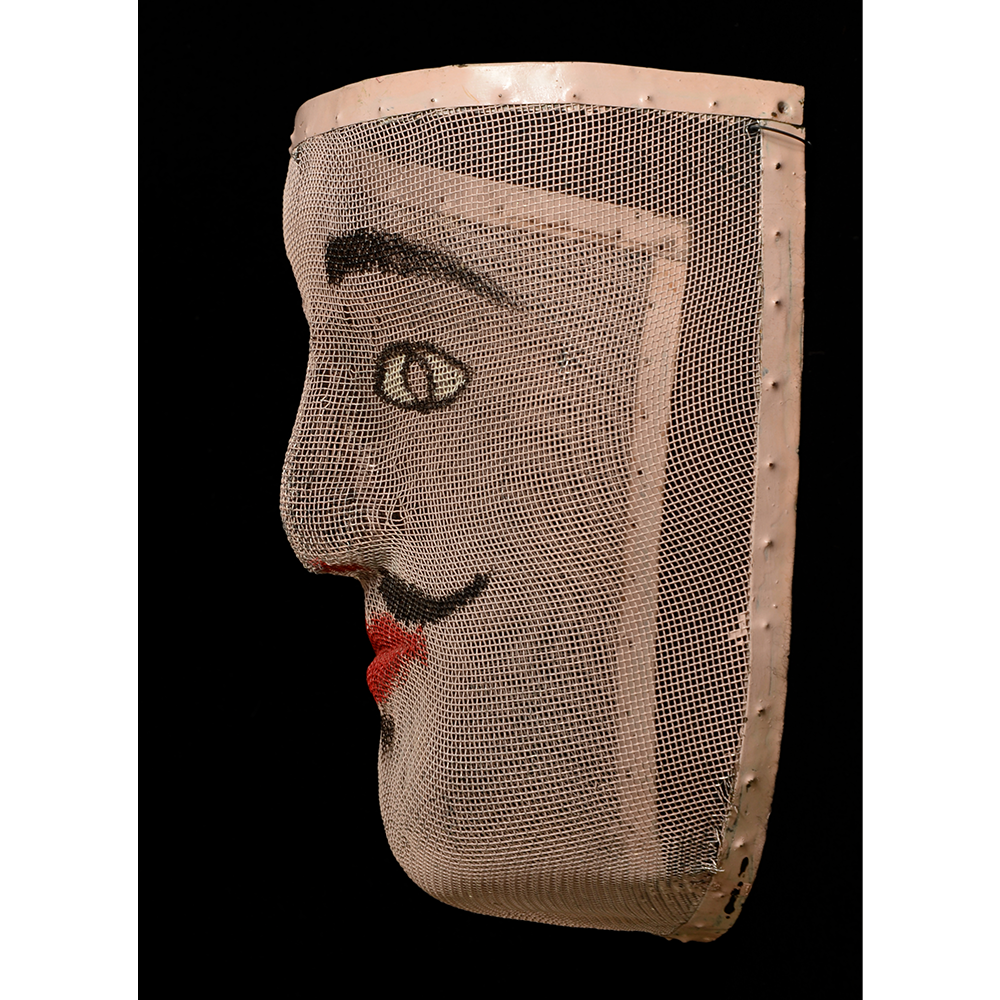

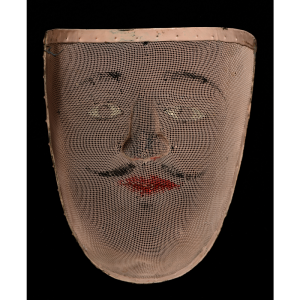

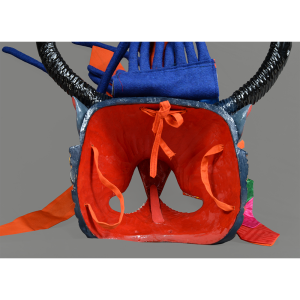

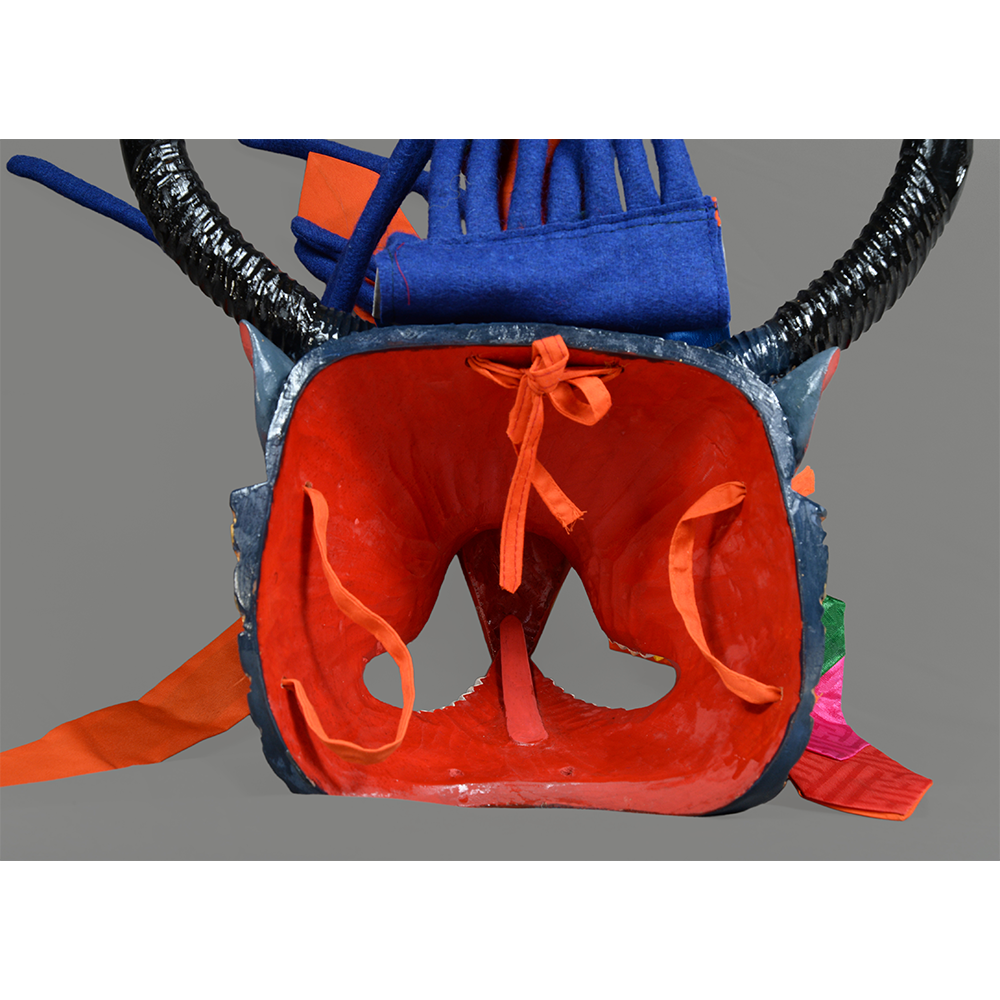

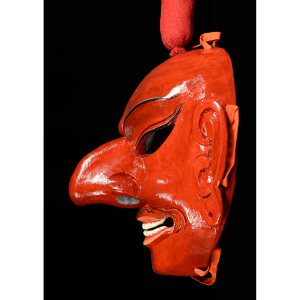

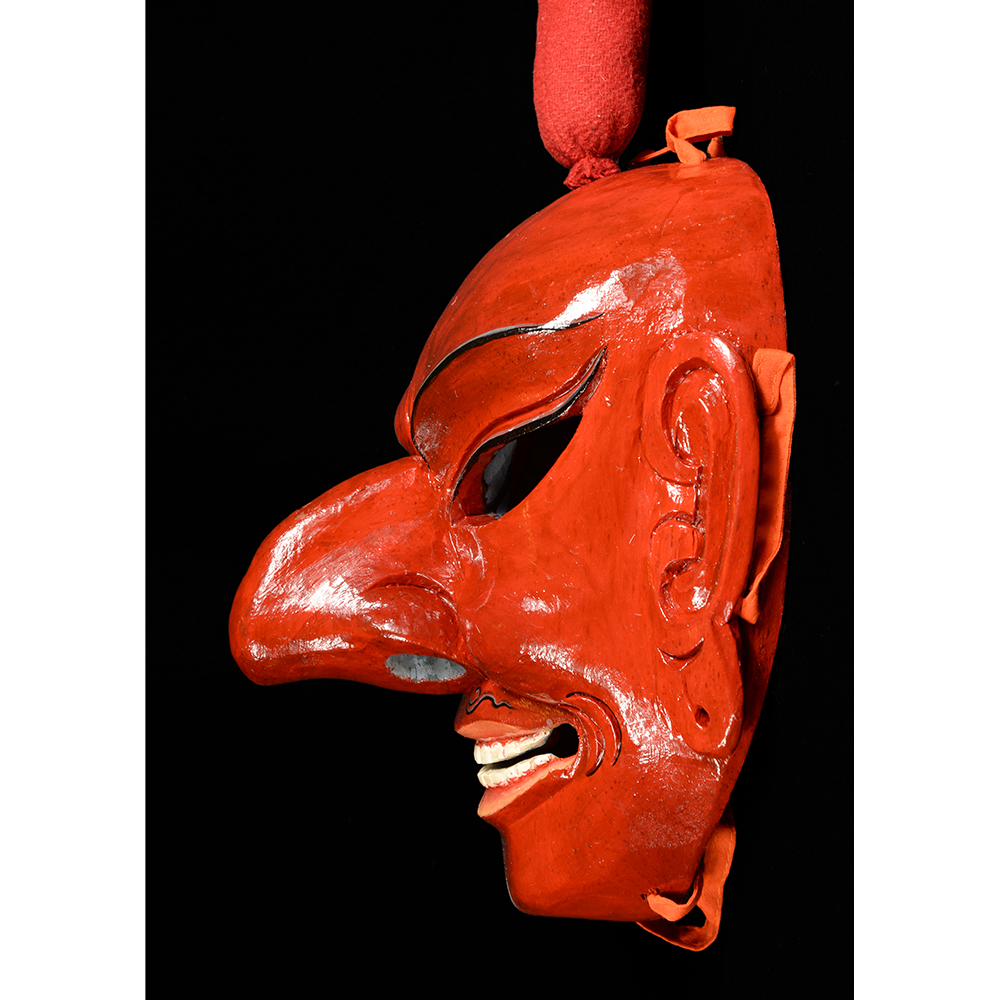

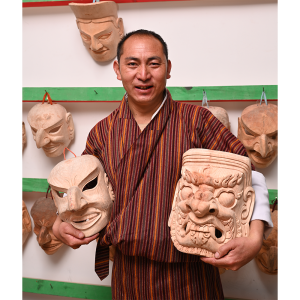

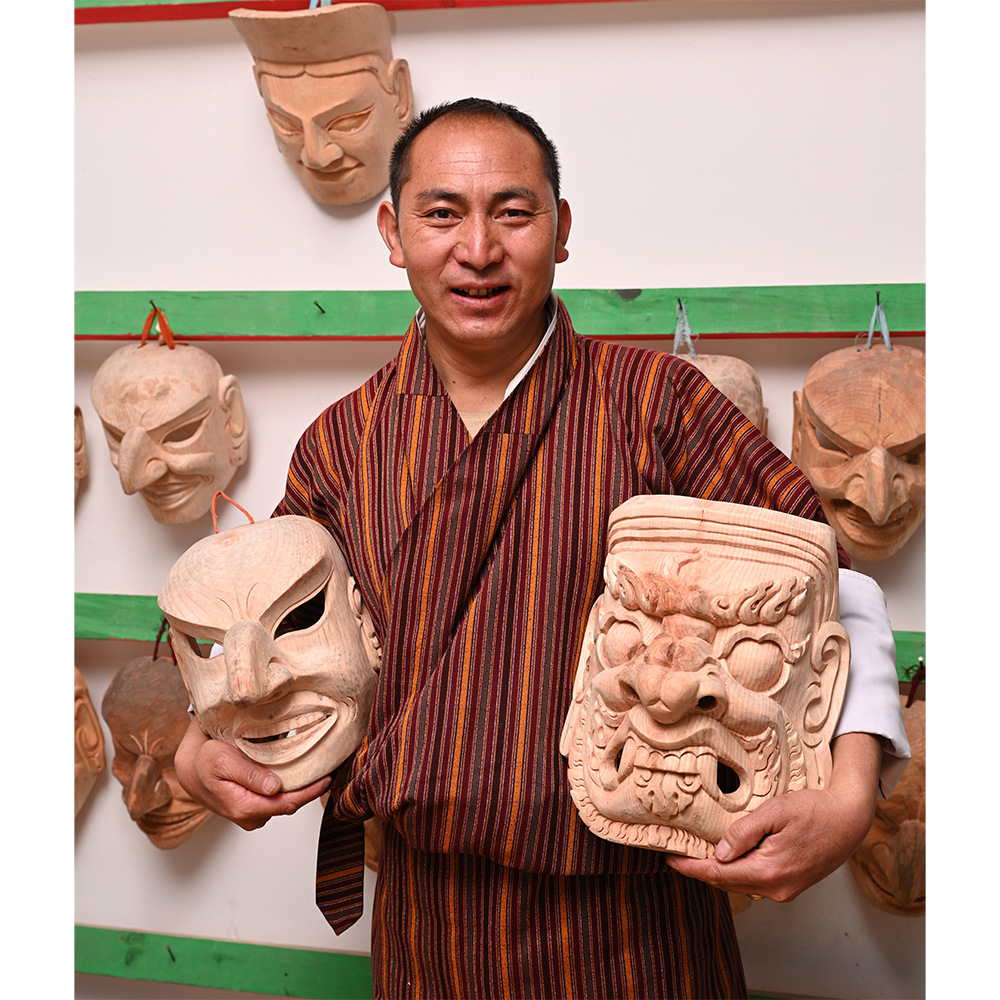

TITLE: General Zhangfei Nuo Mask

TYPE: face mask

GENERAL REGION: Asia

COUNTRY: China

SUBREGION: Guizhou

ETHNICITY: Hmong (Miao)

DESCRIPTION: Nuo mask of General Zhangfei for the Three Heroes Fight

CATALOG ID: ASCN018

MAKER: Zhou [first name unknown] (Cha Tou Pu Village, Pingba City, Anshun, 1934-2012)

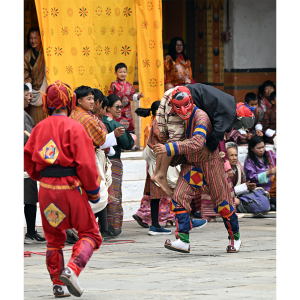

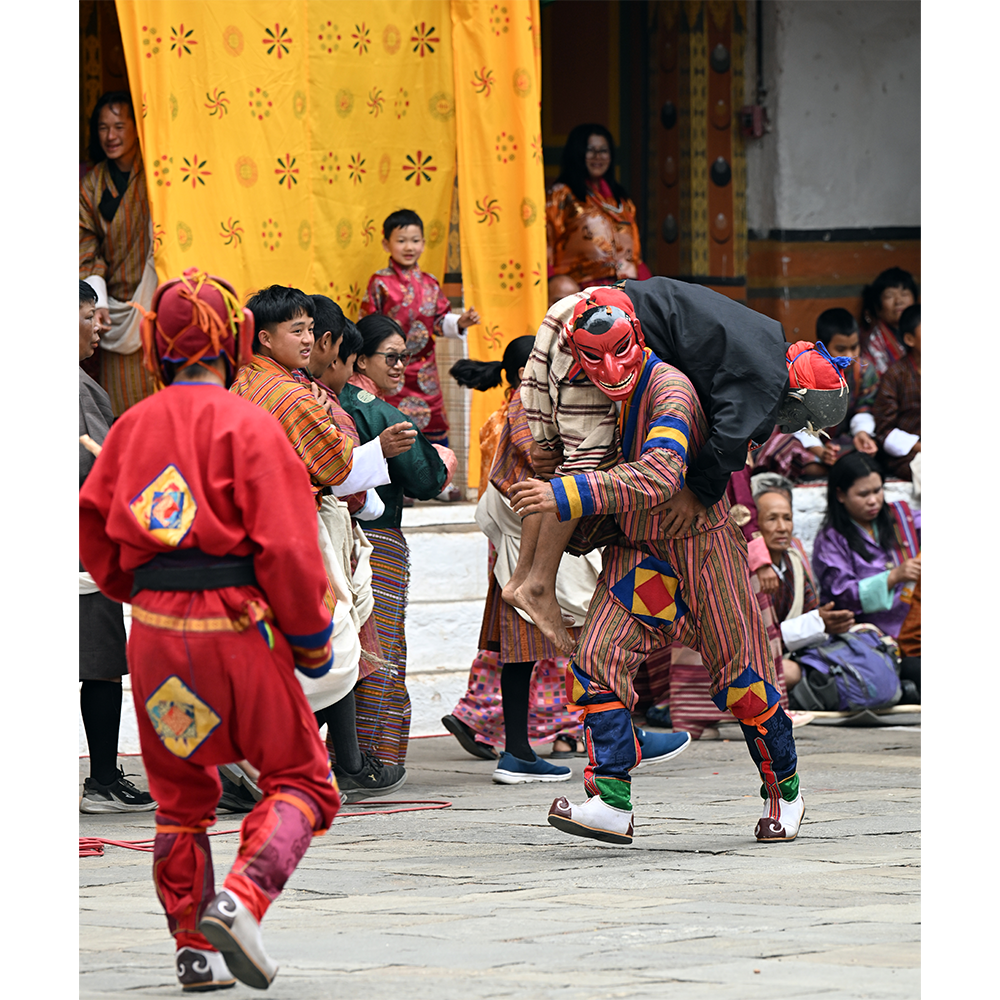

CEREMONY: Nuoxi

FUNCTION: Celebration; Entertainment; Protection/Purification

AGE: 1980

MAIN MATERIAL: wood

OTHER MATERIALS: paint; string; human hair; adhesive; mirror; rubber bands; decorations of dyed cotton; bamboo; artificial pheasant feathers

The Nuoxi of China may be traced back to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE), possibly much earlier (some believe the Shang and Zhou Dynasties) and was popular in large parts of the empire, but especially along the southern borders, where it was a form of entertainment for the imperial troops. It evolved from a sacrificial rite performed by shamans into a more dramatic form, with both Buddhist and Taoist overtones. Nuo opera is based on historical stories and stories based on the Taoist religion and all roles (including female roles) are performed by men. It evolved into a popular form of entertainment and was eventually accompanied by an orchestra of Chinese instruments. The Nuo opera never quite lost its shamanic connection, however, and also was used to exorcise evil spirits at the home of sick persons. The sacred connection is evident from a religious ceremony that always precedes the opening of a Nuo opera. In addition, a wooden statue representing the originator of the opera is present at every performance, and nobody except the opera troupe may touch props used in the performance. Although the Chinese Communist Party attempted to suppress Nuo performances and eliminated it from most of the country, the opera continues to be performed in three southern provinces of China today (Guangxi, Guizhou, and Jiangxi).

The Miao people are part of the Hmong ethnic group living in southern China. The hair on Miao nuo masks must be cut from the corpse of a man who had several children and who lived an exemplary life, neither feuding with neighbors nor hoarding wealth. This character, General Zhangfei, is used in a dance-drama from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms called the Three Heroes Fighting Lu Bu. It is supposed to recount the story of three brothers who fought General Lu Bu at the Hu Lao Pass, Henan, around 190 CE. According to different versions of the story, the brothers attacked Lu Bu because of his reputation as the greatest fighter in China. After a long battle, they overcame Lu Bu and forced him to retreat to the pass gate. In another version of the story, the brothers overwhelm Lu Bu, with Zhangfei delivering a wounding blow, and they befriend the surrendering Lu Bu.