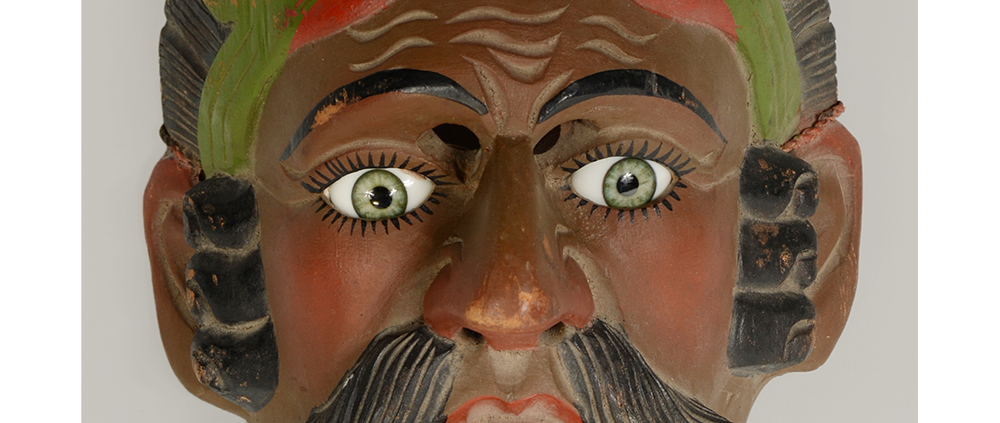

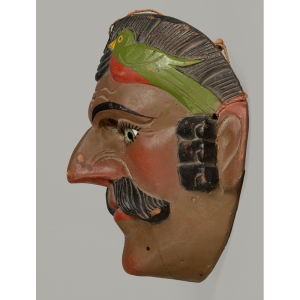

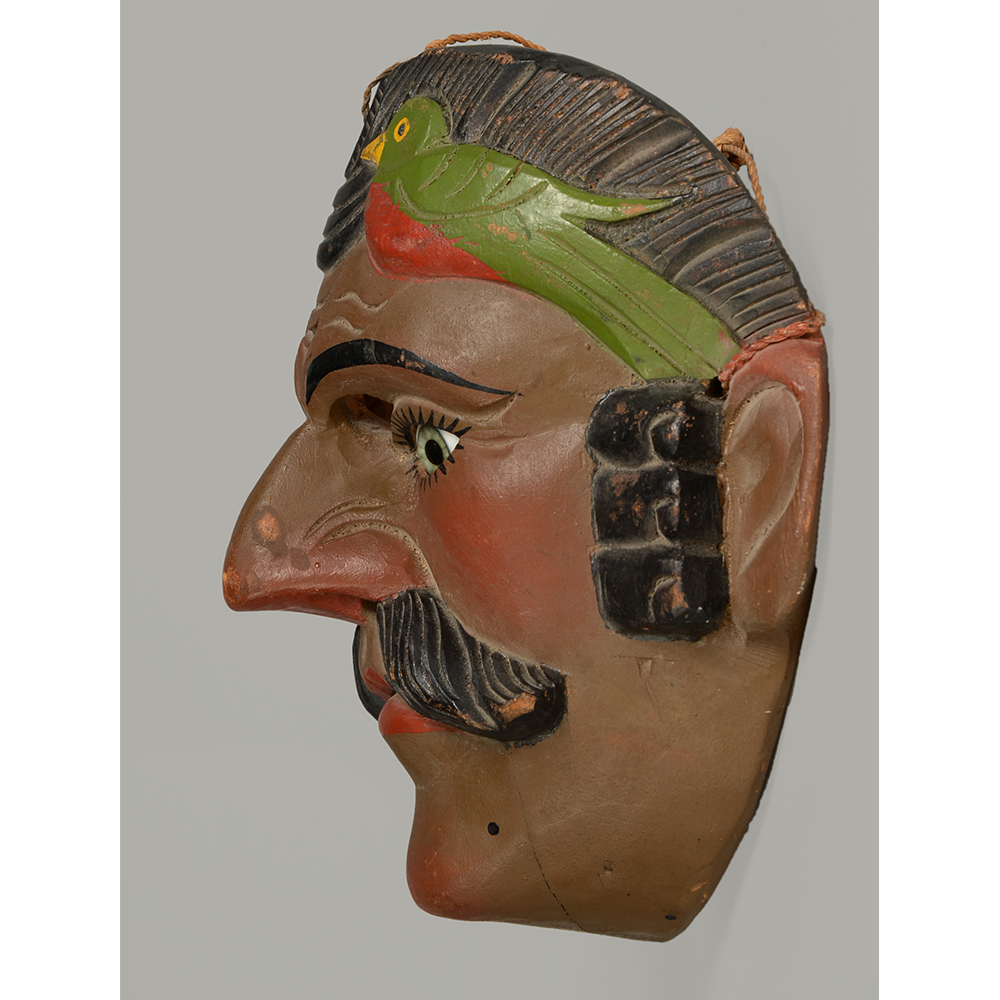

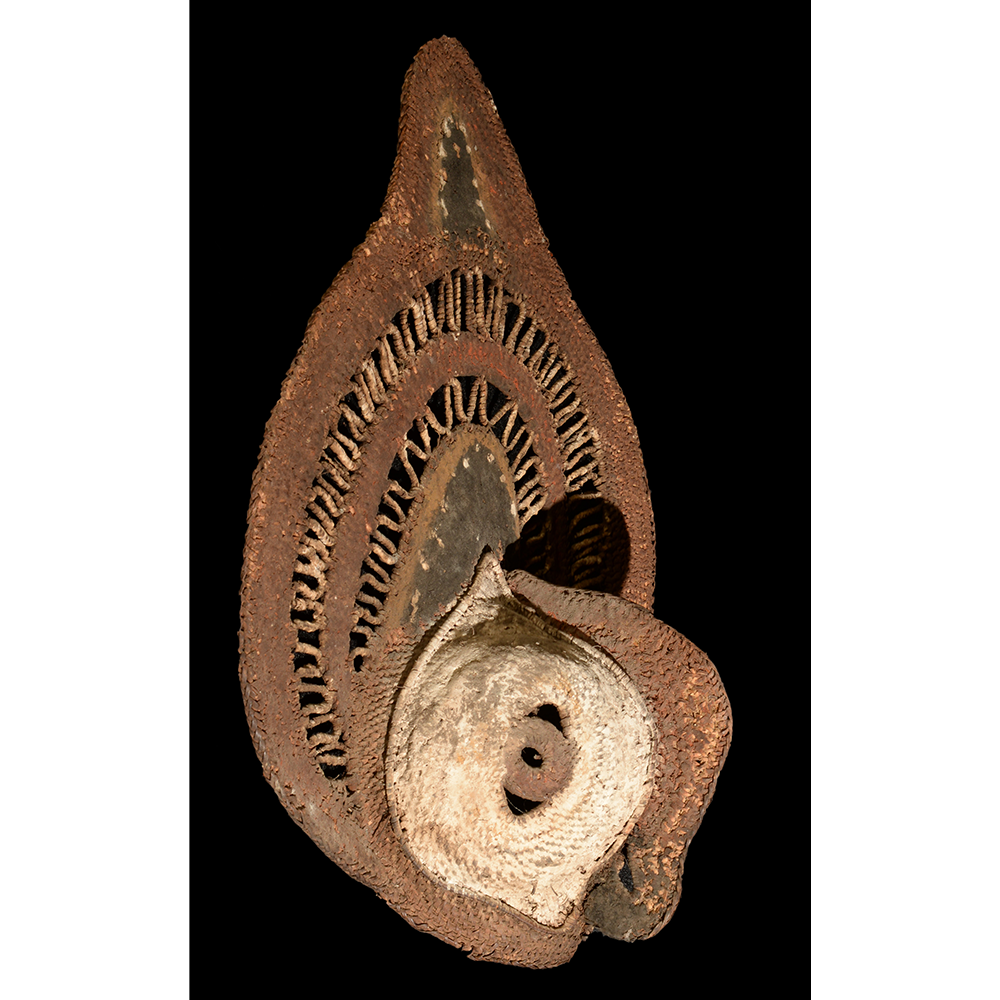

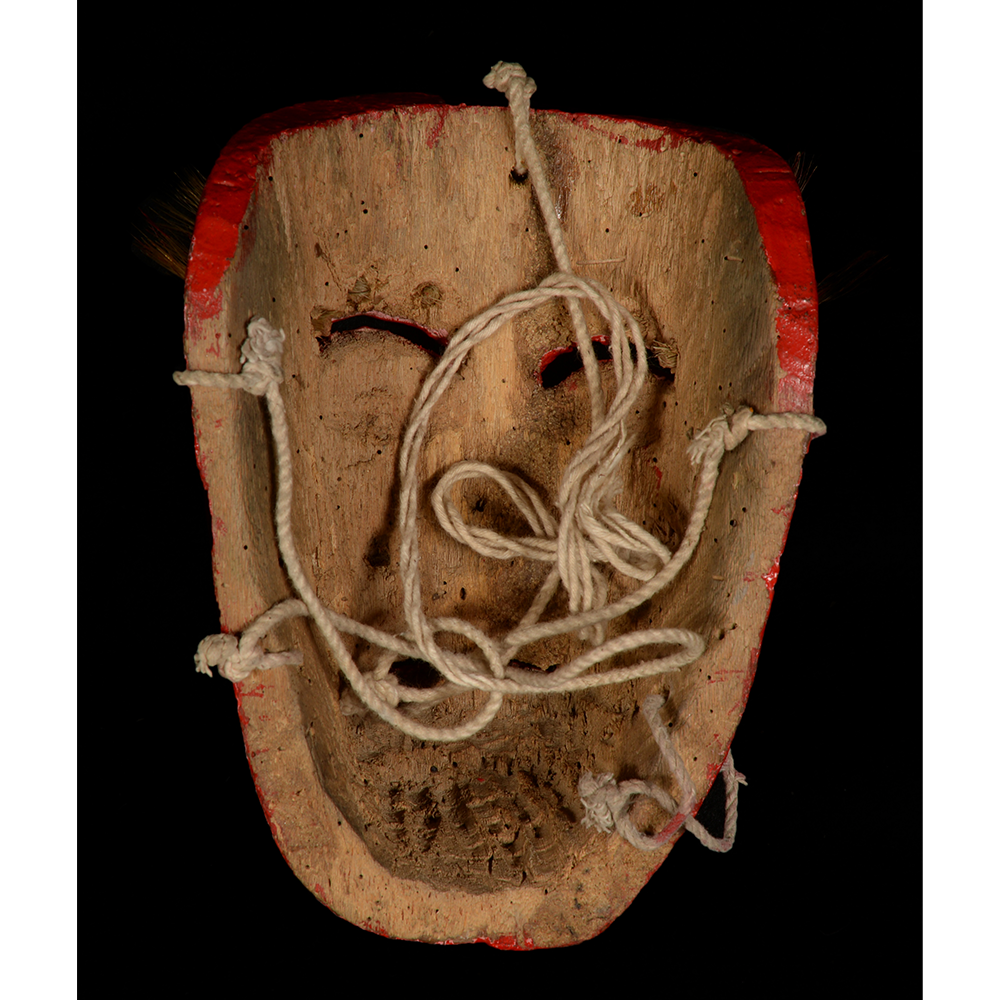

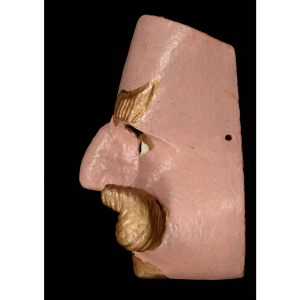

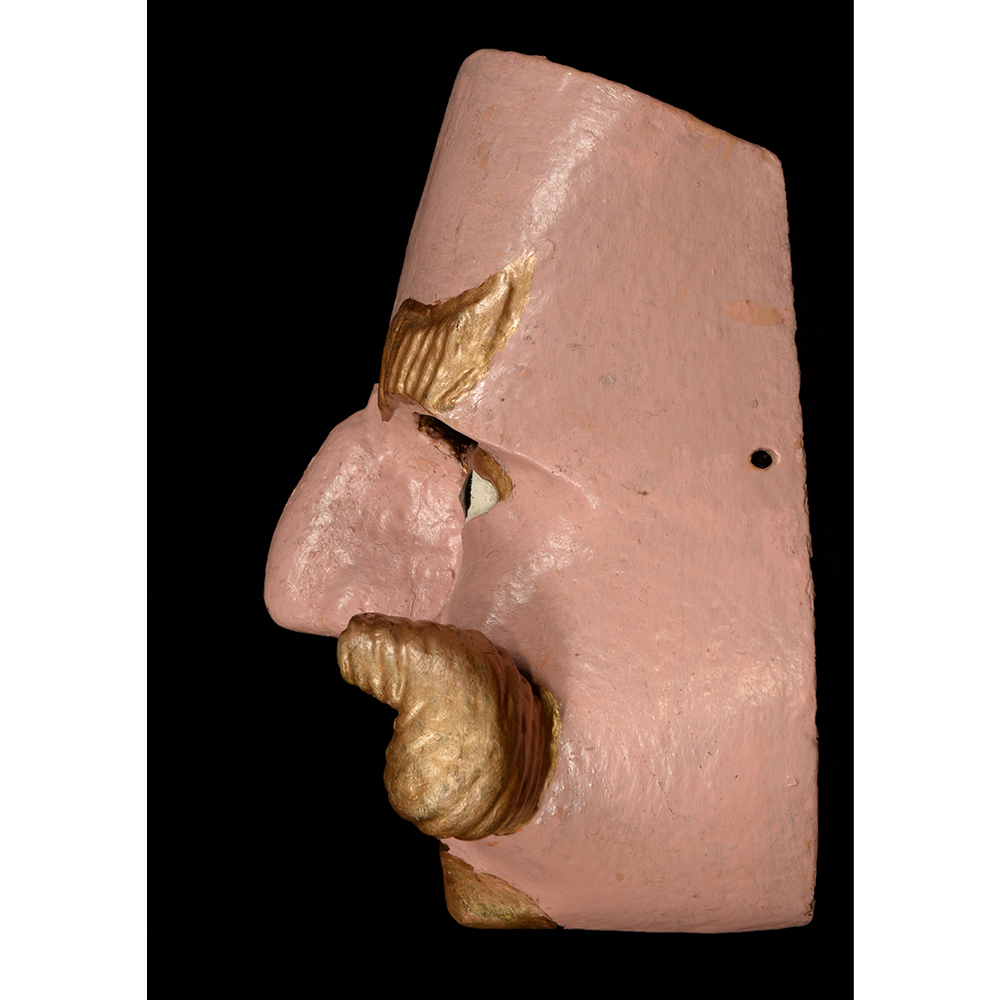

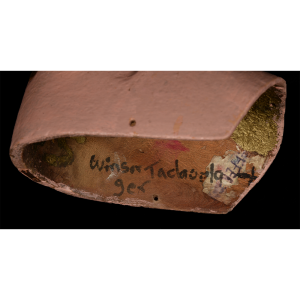

TITLE: Mam (Lucas) Mask

TYPE: face mask

GENERAL REGION: Latin America

COUNTRY: Guatemala

SUBREGION: Baja Verapaz

ETHNICITY: Mayan (Achí)

DESCRIPTION: Mam (Old Man) Mask of Lucas

CATALOG ID: LAGT010

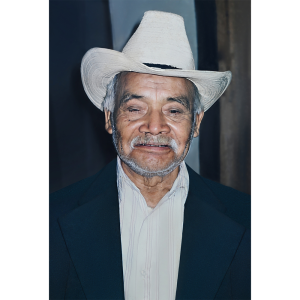

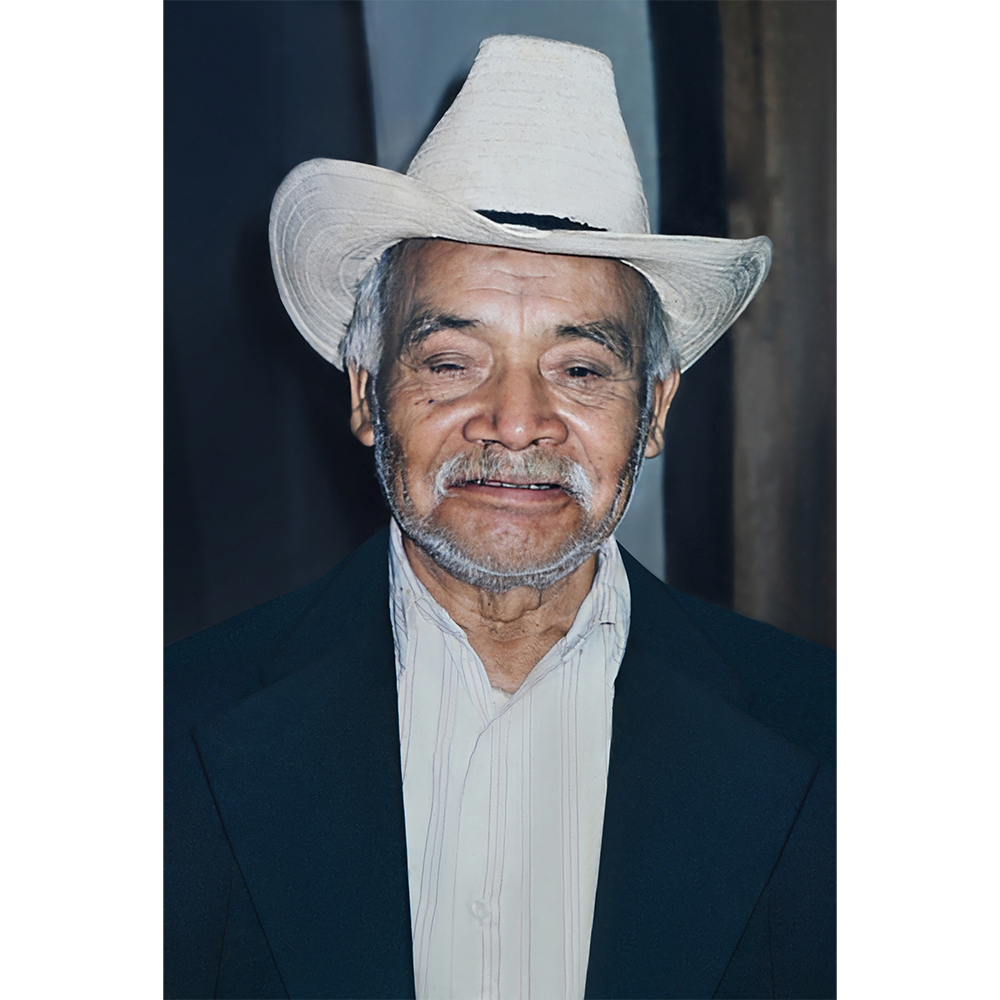

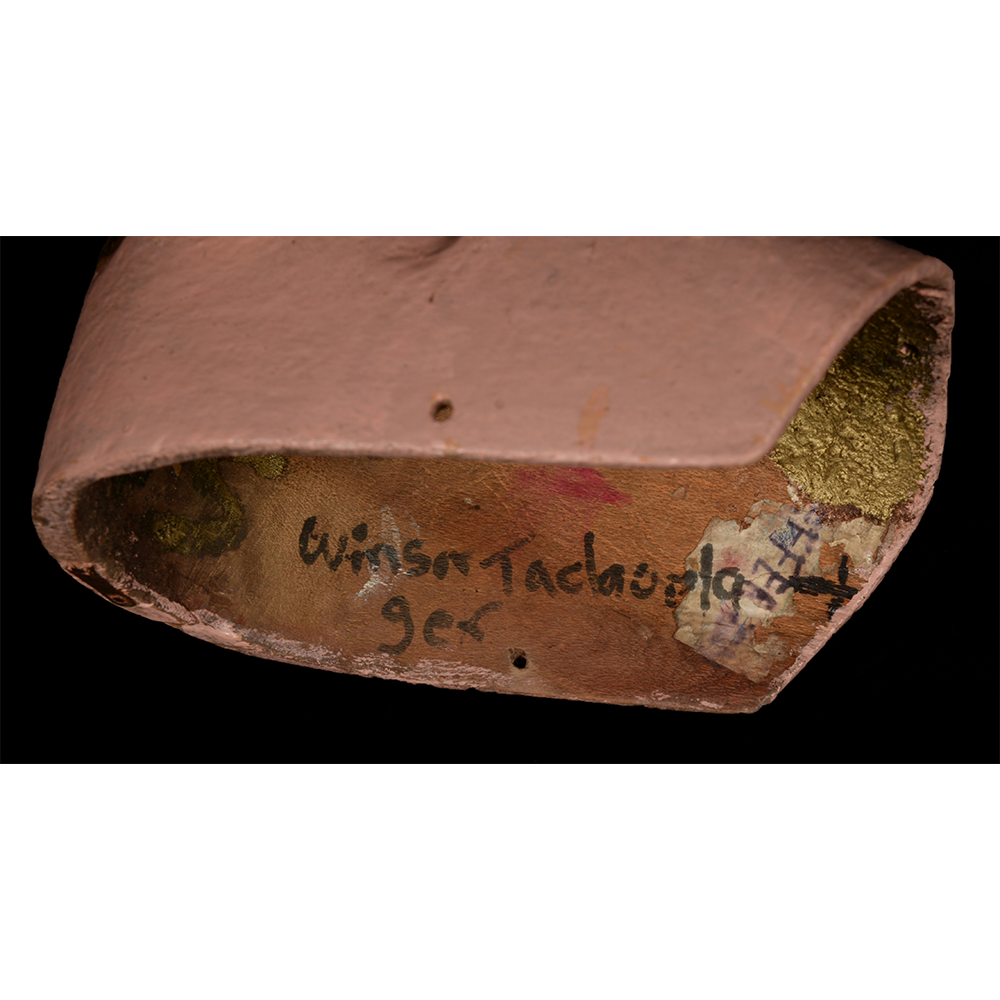

MAKER: Juan Chen Ordóñez (Rabinal, 1926-2017)

CEREMONY: Baile de los Costeños (Baile del Costeño)

AGE: 1990

MAIN MATERIAL: wood

OTHER MATERIALS: dyed agave fiber hair; oil-based paint

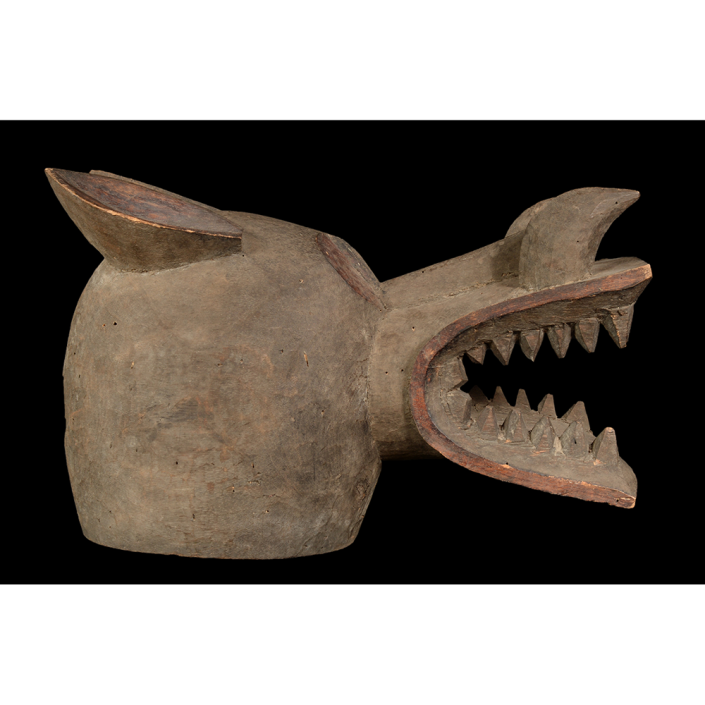

Baja Verapaz, Guatemala, has numerous masked folk dances. Among them is the Baile del Costeño, sometimes called the Baile de los Costeños (Dance of the Coastal People), which is an early colonial dance-drama. The dance usually has 12 characters, divided into four buyers have come inland to exchange cocoa for cattle (maxeños, or cargadores), and six sellers of cattle, who are cowboys. The buyers are Cristóbal (the boss), Pablo (1st buyer, in a red mask), Ratón (2nd buyer, in a black mask), Mundo (3rd buyer). The vaqueros are Pascual (the boss), Tomás, Gaspar, Juan, Lucas (Mam, in a red mask with whiskers), and El Torito. Except for Lucas, the vaqueros wear flesh-colored masks with blue chins and gold eyebrows. There are also three more characters: La Panchita (wife of Lucas), El Torito, and El Miquito. Several of these names are evocative of comical characteristics of the dances. Ratón means “Mouse,” Mundo means World, La Panchita means “The Little Stomach.” The dancers are accompanied by music from three marimba players.

In the drama, the sellers arrive in Rabinal during a holiday to unload their cattle for cocoa. They bring with them a beautiful woman, La Panchita, who is the wife of Lucas (represented by this mask), an old man. The cowboys have brought with them a little bull (El Torito) and the buyers have a little monkey (El Miquito), and together they have a mock bullfight for fun. Meanwhile, La Panchita has prepared food for the group, and soon the buyers, who have become drunk, start bothering La Panchita. Lucas then fights them off with a whip (chilío). Nonetheless, La Panchita shows some favor to the third buyer (Mundo), who has the group’s money. The dance ends when the leaders of each group, Cristóbal and Pascual, bargain to exchange the cocoa and cattle (symbolized by El Torito). The bull is branded by the buyers, and then they return to having a bullfight. At this point, they tell the story they have enacted in speeches, and then take their leave of the marimba players, thus ending the dance-drama. The whole proceeding takes about two to two-and-a-half hours.

For more on Guatemalan masks, see Jim Pieper, Guatemala’s Masks and Drama (University of New Mexico Press, 2006).