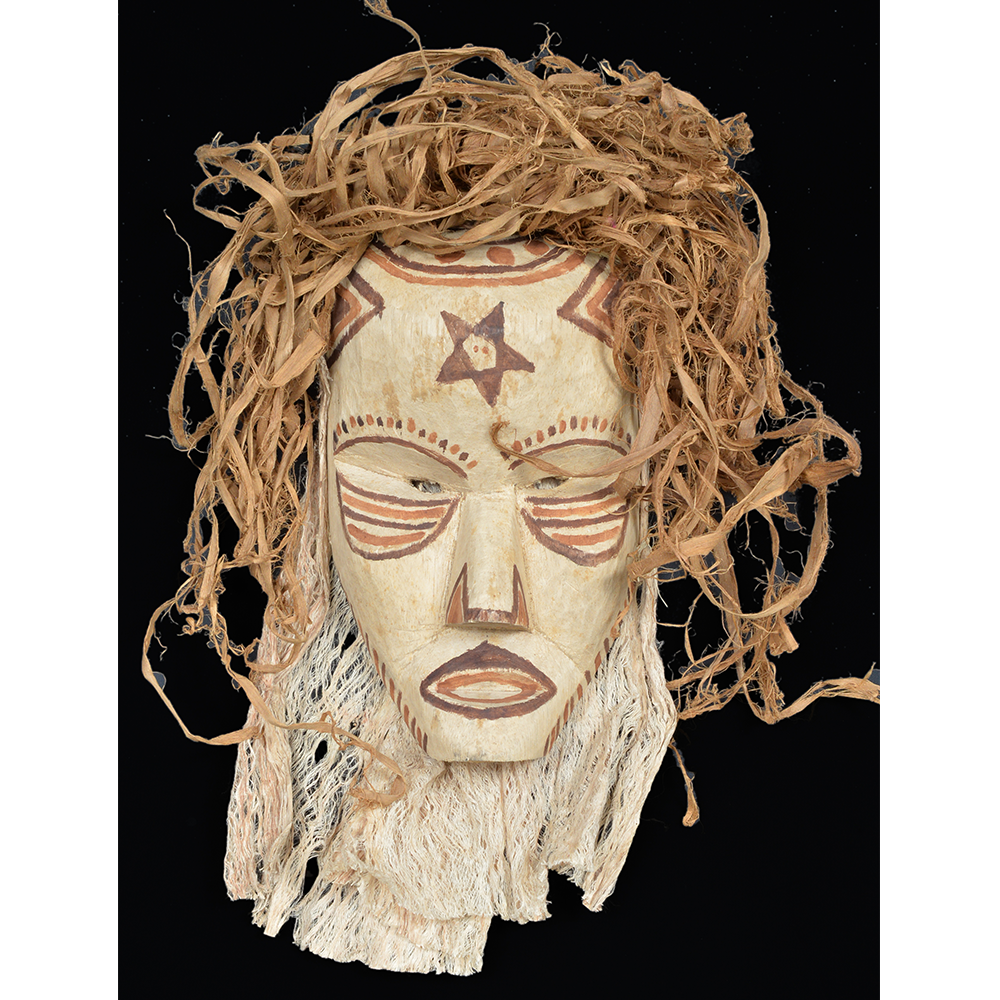

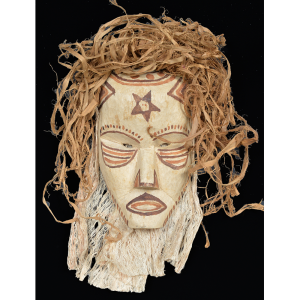

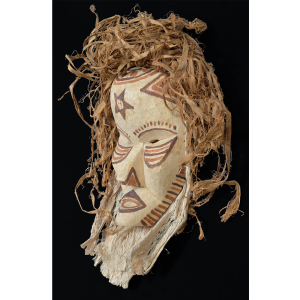

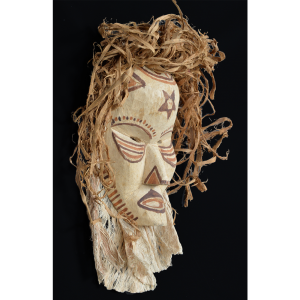

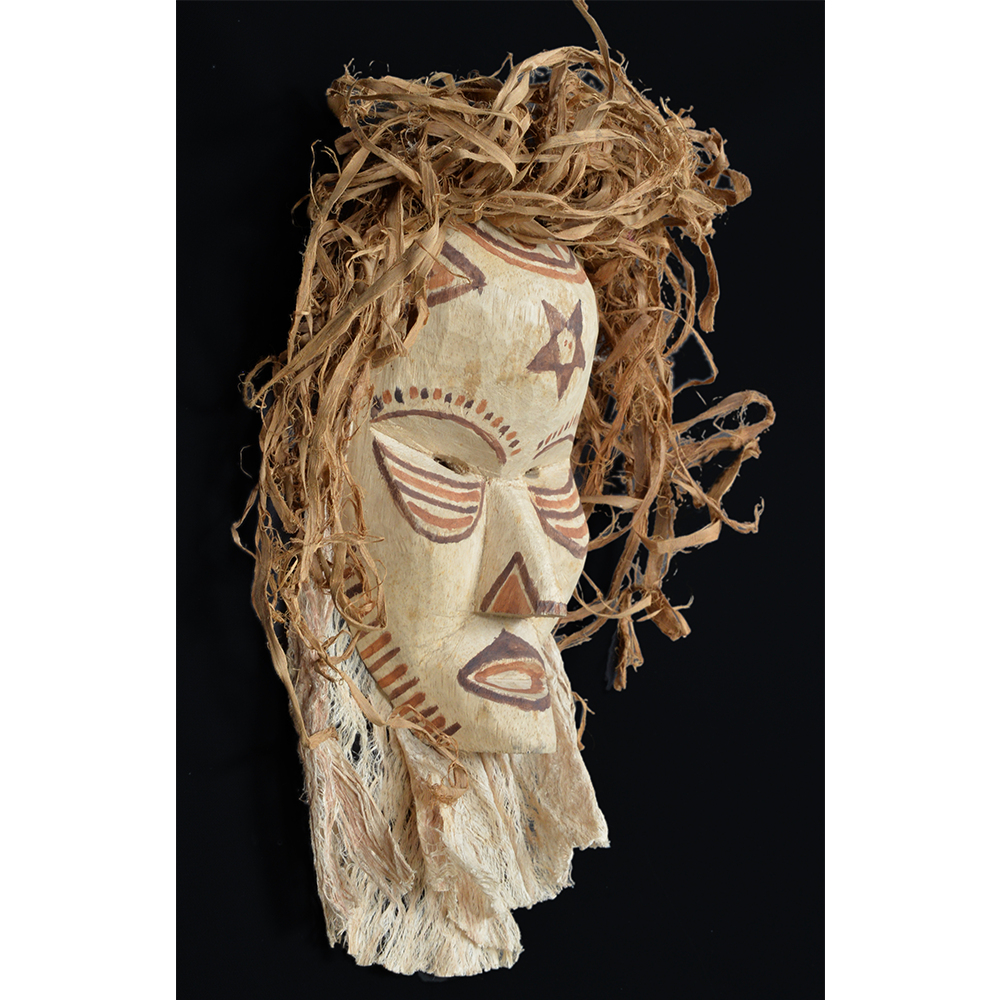

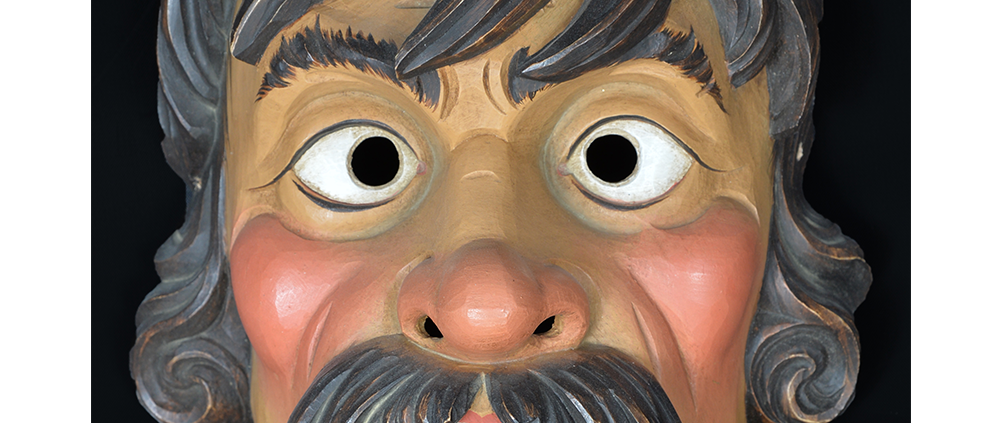

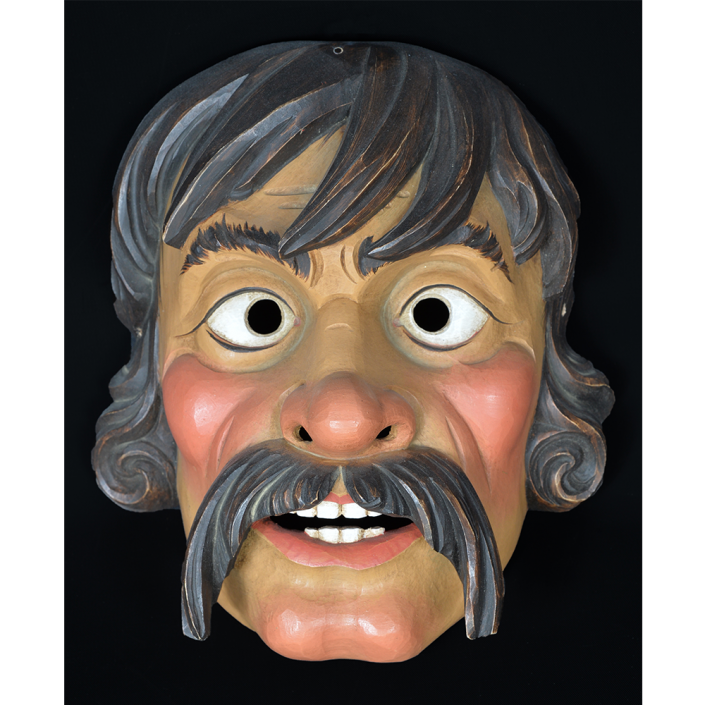

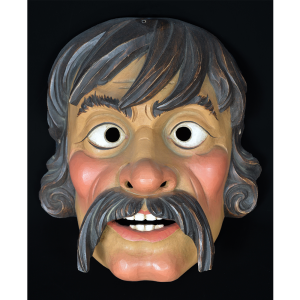

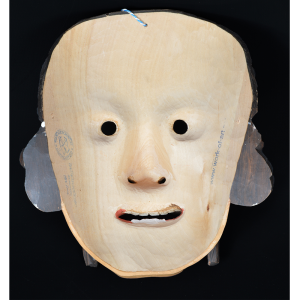

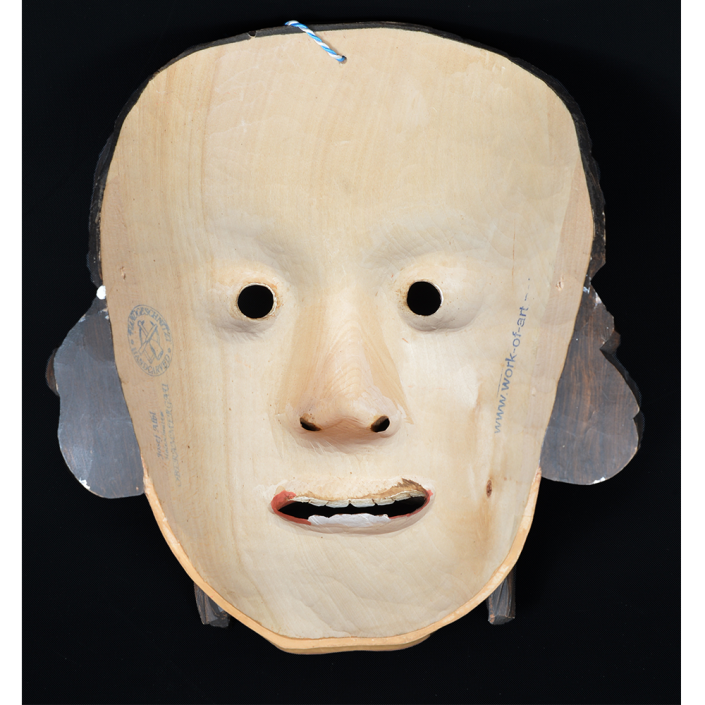

TITLE: Ticuna Shaman Mask

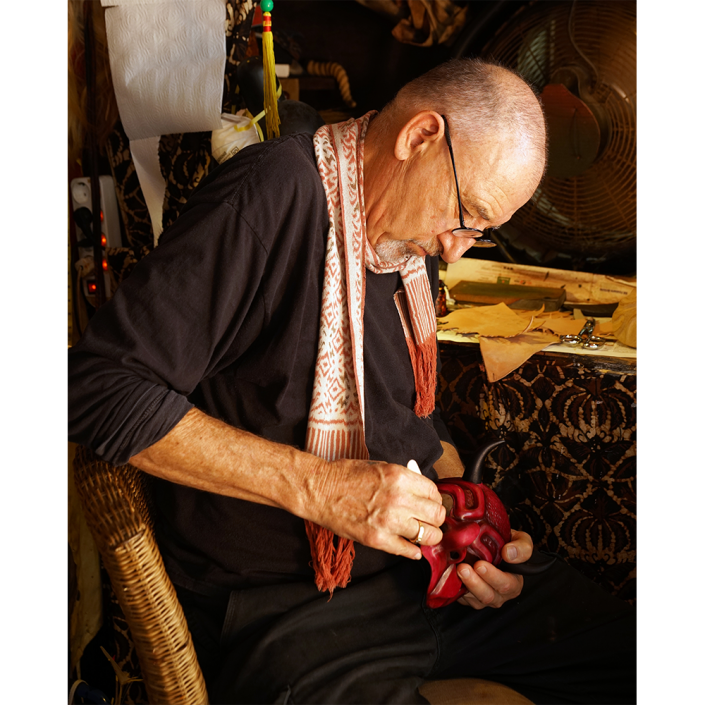

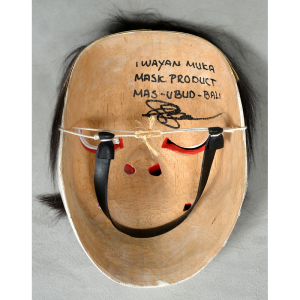

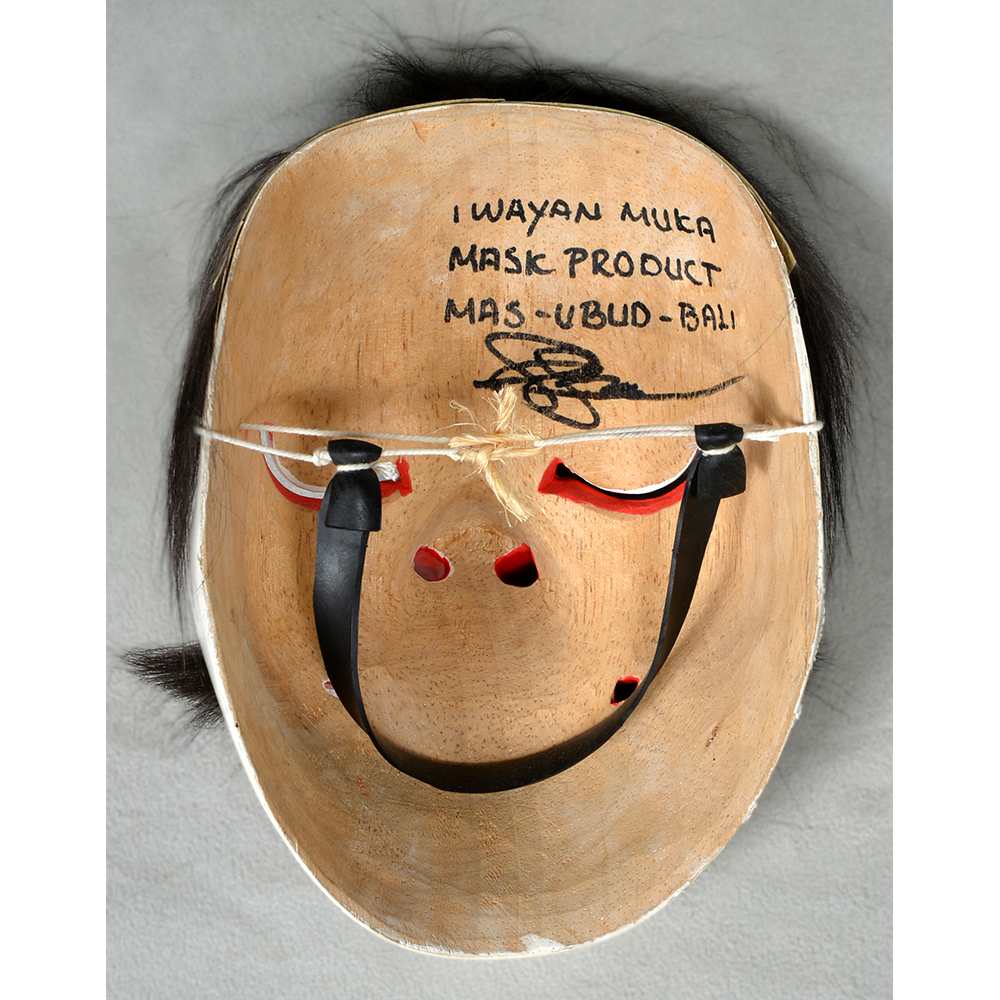

TYPE: face mask

GENERAL REGION: Latin America

COUNTRY: Brazil

SUBREGION: Amazonas

ETHNICITY: Ticuna

DESCRIPTION: Shaman Mask

CATALOG ID: LABR004

MAKER: Unknown

CEREMONY: Adult Initiation

AGE: ca. 1990s

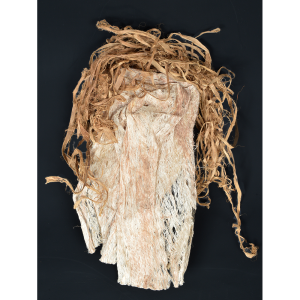

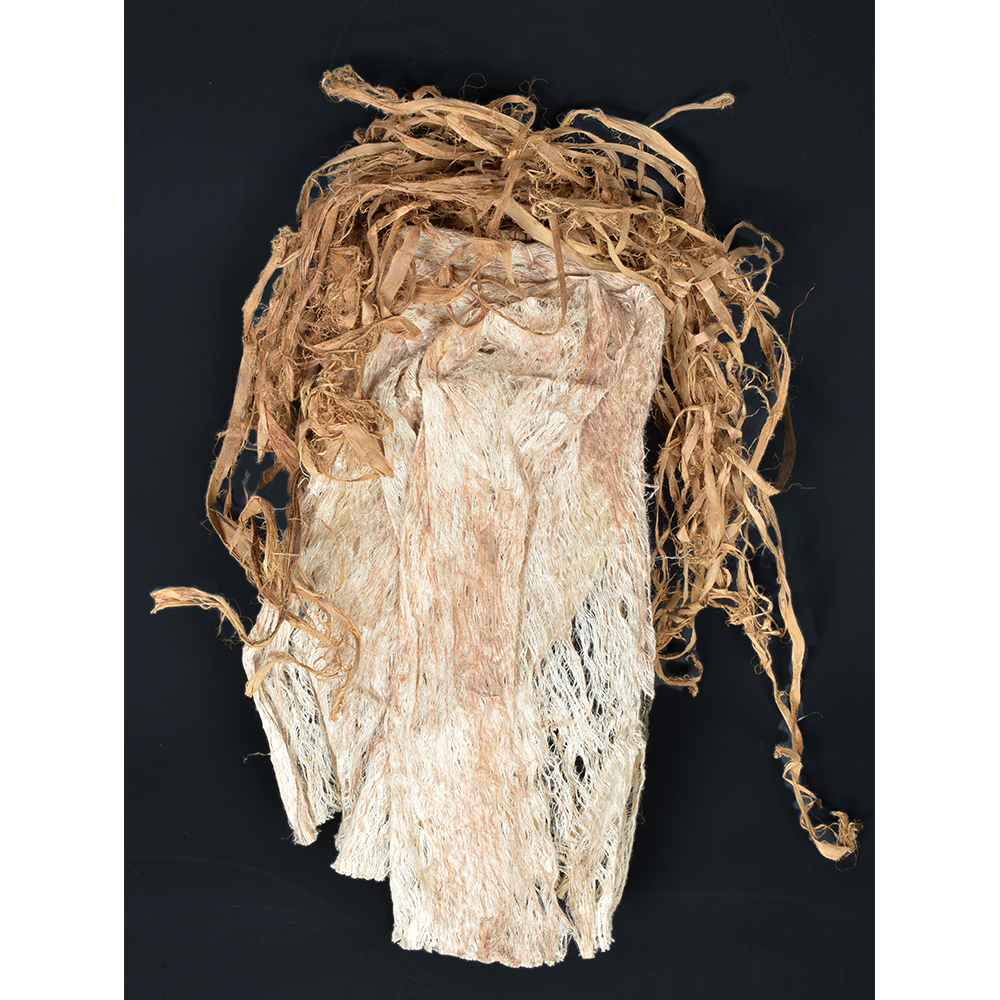

MAIN MATERIAL: wood

OTHER MATERIALS: bark cloth; plant fiber; pigment

The Ticuna people of the Amazon rain forest populate large parts of the Amazonas state of Brazil, as well as parts of Colombia and Peru. Brazil finally recognized the Ticuna right to control over some of their historic lands in 1990. Men make and use all Ticuna masks, are used primarily in adult initiation rituals for girls and in funerals. Funeral masks always represent animals that the deceased would want to hunt in the next life. Human masks are part of a full body suit made of tapa (cloth made from pounded tree bark) and are danced at an elaborate ceremony for the initiation of girls into adulthood. This specific mask was almost certainly made for the tourist trade.