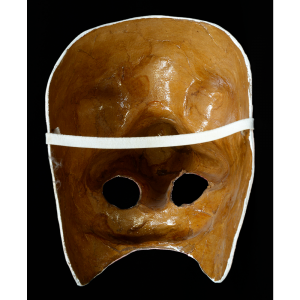

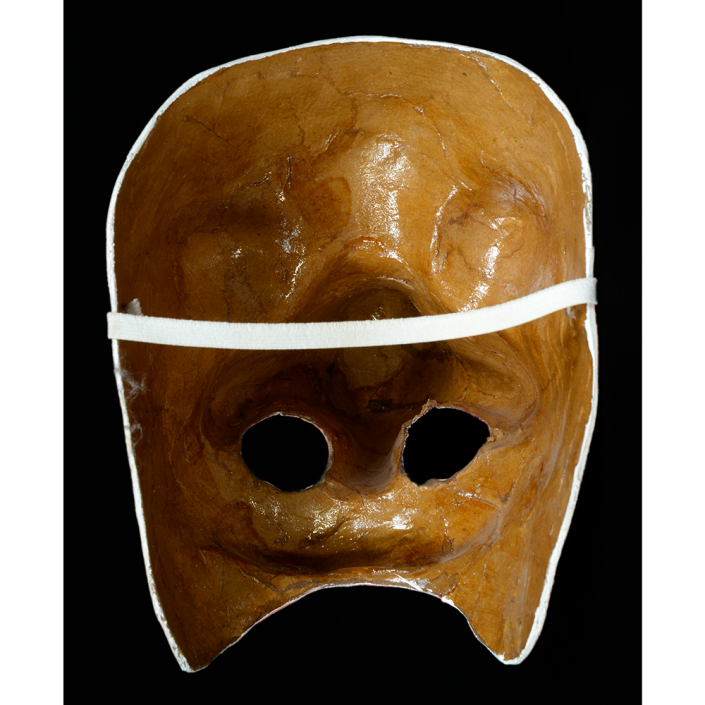

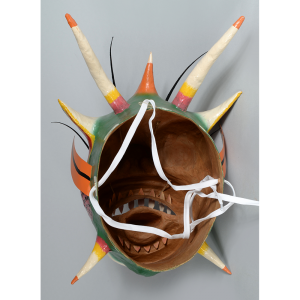

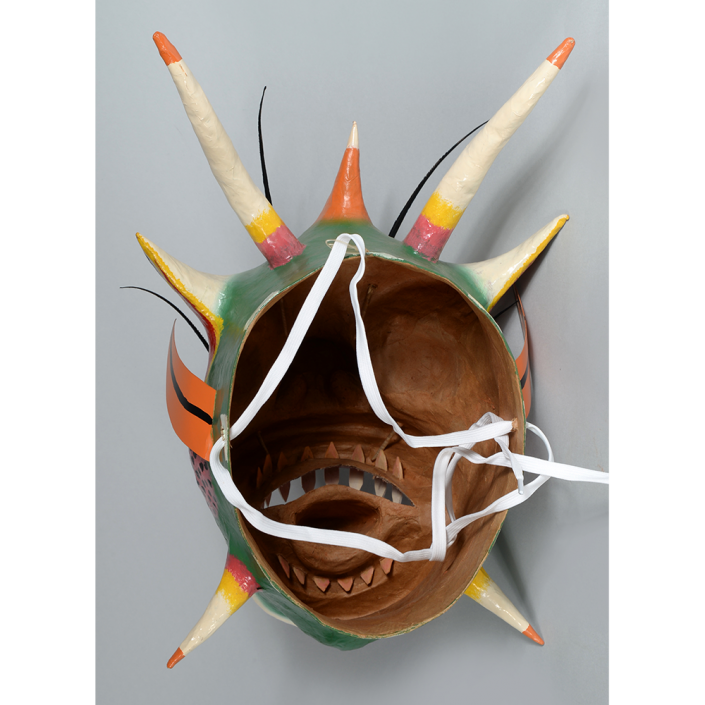

TITLE: Basler Carnival Half Mask

TYPE: face mask

GENERAL REGION: Europe

COUNTRY: Switzerland

SUBREGION: Basel

ETHNICITY: Swiss

DESCRIPTION: Carnival Half-Mask for Fife Player

CATALOG ID: EUCH004

MAKER: Unknown

CEREMONY: Fasnacht (Carnival)

AGE: 1990s

MAIN MATERIAL: paper maché

OTHER MATERIALS: paint; elastic band; hardware; dyed cotton cap

Fasnacht is what the Tyrolean Swiss call Carnival. In many towns in Austria, southern Germany, Switzerland, and northern Italy, local folk don elaborate masks and costumes to parade through the town. Different towns have variations on the parade, such as the Schemenlaufen of Imst, the Schellerlaufen of Nassereith, and the Muller and Matschgerer of Innsbruck, Austria.

In Basel, Switzerland, masks are almost all made of paper maché and take a helmet form. Armies of costumed clowns, musicians, and dancers, called cliques, parade around town in uniform mask styles for 72 nearly continuous hours on the Monday following Ash Wednesday. The paraders must wear their Larven (masks) throughout the parade and are expected never to remove the mask in order to identify themselves. They throw confetti at crowd members with such proliferation that it blankets the streets.

Although there is a great deal of innovation and creativity in mask styles, there are certain styles that tend to reappear annually. This mask, known as Waggis, represents a big-nosed, frizzy-haired clown, who wears wooden clogs, a blue shirt, and a red neckerchief. He is a prankster who parodies the Alsatian farmers who formerly came to Basel market days to sell their produce (Waggis literally means a person from Alsace in Basel dialect). Other common characters include the Alti Dante (old aunt), Dummbeeter (trumpetist) and Pierrot (a sad clown from the late Italian Commedia dell’Arte, known for his white and black makeup).

This specific mask was made for and used by a fife player in one of the roaming bands. Half masks are common among wind instrument musicians who need to access their instruments with their mouths.