The authenticity of a mask often dictates its value to museums and collectors. But what does it mean for a mask to be “authentic?” In this post, I will discuss the concept of authenticity and what it means and should mean.

Used or Unused?

Some view masks as authentic only if used in a cultural context by the relevant society. A mask used in a performance or ritual is by definition authentic. However, it is a fallacy that an unused mask is necessarily inauthentic. The only difference between a new mask made for cultural use and a used mask of that type may be wear from use, such as sweat stains, abrasions, or chips. Wear may be very light even after long years of use, depending on climate factors and how the mask was used and stored. Japanese Noh masks, for example, may be coated with lacquer on the interior to prevent damage from sweat stains, never touched on the outside during a performance, carefully cleaned after use, and stored in padded boxes between uses. Evidence of use would typically be minimal. Mexican Tastoan masks, in contrast, have an uncoated interior, are used in a vigorous performance involving a real physical battle, and may be stored in the open. Use tends to be evident after a relatively short time.

In either case, however, use does not add to authenticity, in the sense that even a new mask reflects culturally embedded beliefs and production techniques. Only through magical thinking can stains and damage make a mask more authentic. Past use does give a mask “history,” but history is different from authenticity, and history only matters if its specific details are known.

“Authentic” Tourist Trade Masks?

Many masks are made specifically as souvenirs for tourists. It is common to view such masks as inauthentic, and frequently they do not closely resemble masks made for actual use. However, morphologically, such masks may be as authentic as any culturally used mask. Many of the higher quality tourist masks are indistinguishable from masks made for actual use, with the possible exception of missing attachment holes, straps, or accouterments. Because the intentions of the maker may be irrelevant to the characteristics of the mask, such masks may well be an authentic cultural expression.

Tourist trade masks do sometimes differ from masks intended for cultural use in the intangible rituals and procedures accompanying their production. For example, in commissioning a new Rangda mask for the village temple, a Balinese priest might use religiously significant procedures, such as choosing a special tree based on the direction of a burl and blessing the ax (or chainsaw!) used to cut it. These steps would obviously be omitted in a mask made for sale to tourists. The omission of such procedures does not necessarily affect the morphology of the mask, and therefore is irrelevant to its authenticity.

Decorative Masks

Many masks made for the tourist trade do not closely resemble masks intended for cultural use. In a sense, all such decorative masks are inauthentic as cultural artifacts. Some depart from traditional archetypes because they express the idiosyncratic aesthetic sense of the maker. These may still qualify as culturally relevant folk art insofar as they syncretize the artist’s individual sensibility with his or her culturally conditioned perspectives and artistic techniques. Although cultures differ in their tolerance for creative divergence from traditional archetypes, the moment a mask no longer conforms to the outer limits of a recognizable archetype, it ceases to be a cultural artifact and becomes a primarily individual expression. Such folk art may nonetheless be aesthetically pleasing and culturally interesting.

Other masks are simply made for crass commercial purposes, sloppily mass-produced to maximize revenue with minimal effort. African, Asian, and Latin American folk art markets in major cities are replete with such masks. Such masks are authentic solely in the sense of being artifacts that document a cultural transition from insular traditions to global capitalism. They reflect less the culture’s tradition than its dilution.

“Fakes”

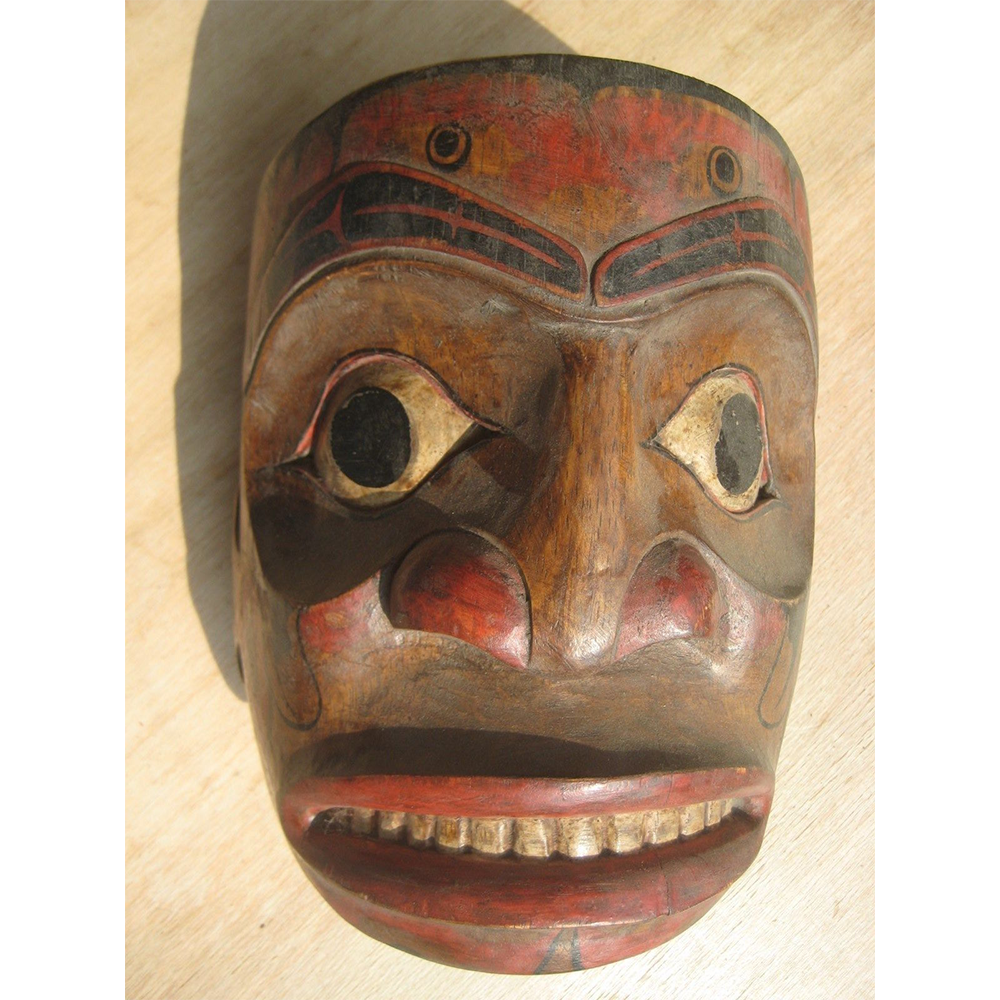

Finally, there are masks produced outside of their original culture for purposes of profiting from the popularity of another culture’s artifacts. Indonesian carvers commonly mimic valuable northwest coast Indigenous American masks, and even the rare masks of the Dayak people of Borneo, for these purposes. Such masks are inauthentic in every sense, because they are not genuine expressions of the culture mimicked nor express the socialized viewpoint of any member of that culture.

—Aaron Fellmeth, Chief Curator