Masks in preliterate societies, before and after colonization.

Painting by Wells Sawyer (1896) of a mask from the extinct Calusa people, who once inhabited what is now southern Florida, United States but were exterminated by Spanish invaders.

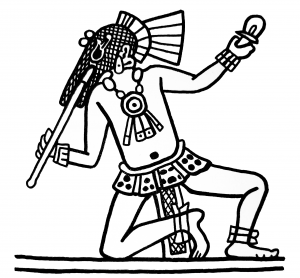

Cultural masks are known to have been worn long before human beings developed written language. Many types of masquerade used by preliterate societies have disappeared from history, frequently along with the societies themselves. In many cases, only archaeological fragments, drawings, or photographs remain to tell us what the masks looked like and give a sense of how the societies used them. It is known that the ancient peoples of the Americas used masquerade in war, religion, and entertainment, although the only surviving artifacts are death masks. For example, the Popol Vuh, the origin story of the Mayan (K’iché) civilization, tells how the god-hero twins Hunahpuh and Ixbalanque entertained the lords of the underworld (Xibalba) with dances, including various dances named after animals, such as the weasel (kux) and the armadillo (iboy). Mayan vases show such dancers wearing masks, representing the titular animals.

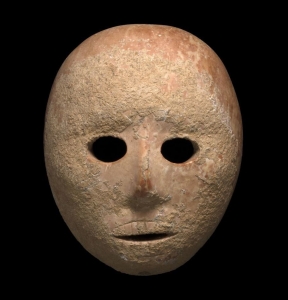

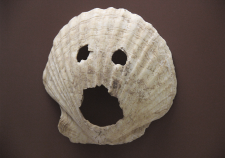

The earliest surviving masks are made of stone or seashell, and were found in the region now known as Israel, Palestine, and Jordan. These date back some 9000 years. Wood masks were probably used for living masquerade much earlier, but, due to weathering, few have survived. The oldest such mask is what appears to be a crest mask representing an aardvark, discovered in Angola and dating back to around 900 C.E.

The disappearance of many ancient masking traditions was assured by the European campaigns of conquest and exploitation in many parts of the New World during the Age of Discovery. Tribal peoples were culled by disease, lethal enslavement, and sometimes genocidal campaigns.

An armadillo dancer plays a flute and shakes a rattle. Drawing from an ancient Chamá (Mayan) vase by Dennis Tedlock.

The Selk’nam, for example, inhabited Patagonia and the Tierra del Fuego region. European settlers invaded their territory in the 19th century and began extensive sheep ranching on Selk’nam hunting grounds. With much of their traditional game gone, the Selk’nam, who lacked any concept of private property, turned to hunting the sheep, which seemed like substitute game to them. Ranchers retaliated by hiring mercenaries to exterminate local tribes. Despite the efforts of missionaries, the Selk’nam quickly disappeared under the onslaught. By 1974, not a single full-blooded Selk’nam was left on the Earth. Their unique culture died with them. (For more on the Selk’nam’s lost masking traditions, see Anne Chapman, Hain: Initiation Ceremony of the Selknam of Tierra del Fuego (Ushuaia, Argentina: Zagier & Urruty, 2008)).

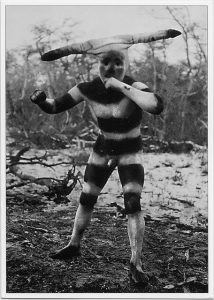

One of the few surviving photos of the Selk’nam people of southern Argentina. Little is known about their masking traditions. Photos by Martin Gusinde, 1920.

Colonialism was not the only source of decline for early masking traditions. In many cases, the ebb and flow of civilizations has resulted in the extinction of societies that existed as independent political entities. Their cultural traditions have disappeared with them. It is likely, for example, that the peoples of East-Central Asia had developed diverse masking traditions before becoming engulfed in the great Mongol Empire under the leadership of Genghis Khan in the 12th century.

Muslim woman wearing a decorative battoulah in Bandar Abbas, Iran. © 2007 by Elena Senao.

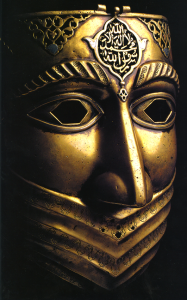

The great Abbasid Arab expansion in the eighth through thirteenth centuries, and Ottoman Turk Empire of the fourteenth until 1924, tended to spread Islam across the Middle East, Central Asia, and North Africa. Late medieval Islamic warriors sometimes wore protective masks that included elaborate decoration. However, Islamic doctrine has generally been interpreted to prohibit figural art representing human beings or animals. The result is that folk masking traditions have largely been stamped out, especially those in which the mask represents gods or spirits. The main exception has been the niqab or burqa worn by Arab women to cover their faces, which is sometimes modestly decorative, as some batula attest. However, properly speaking, the niqab and burqa are not masks but veils; as their purpose is the systematic subordination of women rather than use in cultural rituals.

More recently, the Cultural Revolution in China (1966-76) attempted to eliminate the cultural traditions of Chinese peoples in the service of national unity under a strictly pragmatic Communist ideology. Classic artifacts such as masks used in Nuo cultural drama were destroyed as “counterrevolutionary,” and performances were met with draconian punishments. The Soviet Union also demonized Slavic cultural masking traditions on the same basis from the era of Stalin until its dissolution in 1990.

Even when the cultural identity of the society survives intact, intercultural contact has radically altered or extinguished masking traditions. The Polynesian warriors of Hawaii, for example, were known to wear protective and decorative war masks made of gourds and plant fibers, but these were abandoned after widespread conversion of the islanders to Christianity. Christianity discouraged many cultural traditions, and the adoption of firearms and steel weapons rendered the old protections ineffective in any case. In societies colonized by proselytizing Christians, masquerade was heavily discouraged by missionaries and colonial governments, either outlawed or redirected into Christian themes. For example, pre-colonial masquerade in the Americas was altered so that traditional gods, heroes, and spirits were reinterpreted as devils and demons from Christian mythology, and new heroes such as Jesus of Nazareth and his mother, angels, and saints were introduced to homogenize and indoctrinate colonized cultures.

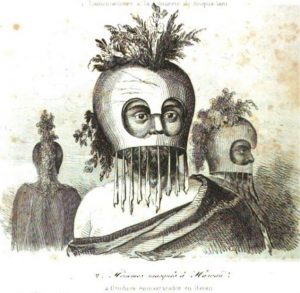

Drawing of Hawaiian warriors wearing traditional gourd masks on first contact with European voyagers, 1834.

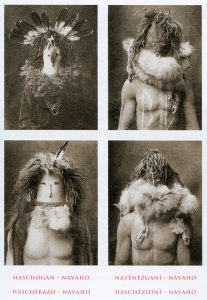

Fortunately, some tribal masking traditions have survived contact with more technologically advanced invaders. The Hopi, Zuñi, Diné (Navajo) and Apache nations of the American southwest, for example, have all preserved their traditions in the face of overwhelming pressures to conform to the customs of colonizers. Masks from such traditions cannot be displayed, because tribal leaders have forbidden images of masked dancers, who are considered sacred when they wear the uniform and mask. Tribal masquerading traditions continue in Africa, Central Asia, and the Melanesian islands of the South Pacific as well, relatively little discouraged by colonization or religion indoctrination.

Persian war mask from the Safavid Dynasty, 16th to 18th centuries.

Edward Curtis took the only known photos of Diné Yeibichei dancers in the first few decades of the 20th century. But for his work, there would be no reliable way of knowing how early dancers looked.

Masks in the ancient world.

Mask of ancient Roman theater. From Francesco Ficoroni, Le Maschere sceniche e le figure comiche d’antichi Romani (1736).

The ancient Greeks and Romans used masks primarily for dramatic performances and entertainment. The early Greek and Roman masks exaggerated the features of the actors so that large audiences could see them clearly, and frequently the mouth had a cone-like shape, like a megaphone, to project the actor’s voice to the upper reaches of the amphitheater. It is thought that some masks even had brass lining in the mouth to further channel and project the voice.

Many Greek and Roman tragedies have miraculously survived the ages, so that they can be read today in substantially the form that ancient actors would have seen them. They notably lack stage directions and costume notes, but we know from first-hand third-party descriptions, engravings, cameos, sculptures, bas-reliefs, and other depictions that actors frequently wore masks. It is likely that the earliest masks were crudely made of tree bark, but as mask-making skills increased, they were made of shaped leather with a cloth backing. They would have fitted tightly over the face, except the megaphonic mouth portion, and probably attached with leather straps. The inability of the actors to communicate with facial expression had to be compensated by bodily gestures and tone of vocal inflection.

Bas relief from the Farnese Palace depicting ancient Roman masked tragedians.

It is also known that, some time during the Roman Empire, scripted tragedies and comedies of the Greek kind began to be supplemented by improvisational pieces, which rapidly became popular with aristocrats because of their ability to deliver topical commentary on the issues of the day, and to make reference to recent political events. Naturally, this also made the actors the target of potential censorship and repression. The masks may have hid their faces, but their identities were well known.

Ancient Asia also seems to have developed masking traditions, initially for religious and ceremonial purposes, but evolving into entertainment. In ancient Japan, Shinto monks created elaborate masked dance rituals known as kagura, a form of ritualized prayer with elements of dance and music. With the influence of Buddhism, monks in the early medieval era adapted kagura into new forms of dance dramas, gigaku and bugaku, which unfortunately did not wholly survive intact the trials of time. They did, however, form the basis of modern Noh theatre. In China, early masked rituals were used to drive away evil and disease and pray for blessings from the gods. These, too, morphed into masked theater, known as Nuo, that influenced Korean and Japanese drama styles and dances, as the close similarity of the names suggests.

Drawings of reliefs from ancient Rome in Ficoroni.

Masks in the Medieval and Renaissance Eras.

In medieval Europe and Asia, masquerade continued to play an important role as entertainment and in promoting cultural solidarity. Chinese and Japanese medieval dramatic masked plays, frequently accompanied by music, developed from their early origins in religious rituals invoking the blessings of the gods into the modern Nuo (China) and Noh (Japan) drama, which has not greatly changed in hundreds of years.

Italian Carnival masks representing Jews with distorted, stereotyped noses. From a 1642 book by Francesco Bertelli, Il carnavale italiano mascherato.

In Europe, although some ancient masking traditions continued, they were transformed by the spread of Christianity. Catholic veneers frequently covered over ancient, pre-Christian pagan masked rituals, with the timing of the rituals adjusted to coincide with major Christian holidays or, when the fit was poor, a holiday in honor of a saint was conveniently made to coincide with the ancient rite. Carnival was one such tradition, and it is well known that Carnival masks of various kinds were worn during the medieval ages. Masks might represent old women, doctors, young lovers, nobles, beggars, foreigners, or characters from the theater entertainment known as Commedia dell’Arte.

Commedia was the successor to Roman theater, masked like its predecessor but having little else in common. Like Roman masks, the Renaissance masks were made of leather lined with cloth, although due to the superiority of later craftsmen, the leather was no doubt thinner and the cloth linen. The Commedia plays were only very loosely scripted, with most of the dialogue invented improvisationally by the actors. It was invented in Italy in the 17th century, but it rapidly became popular throughout Europe, as Italian troupes visited major cities to the north and west, and local imitators and adapters sprouted in France, Germany, and elsewhere to perform the plays in the native language. For some three hundred years, the Commedia reigned as a major form of entertainment in Europe.

An engraving by Maggiotto (Domenico Fedeli, 1713-1794) depicting a Commedia performance with Columbine holding her half-mask, Harlequin, and a Venetian in a “bauta” mask.

Although not every character in the Commedia used a mask, most of the stock male characters did. The masks ensured that the characters—Pulcinella, Il Capitano, Brighella, Arlecchino, Pantaloon, etc.—would be instantly recognizable to the audience, regardless of what actor wore them. Women, in contrast, either went bare-faced or wore a velvet half-mask, as Renaissance women frequently did in real life, to protect their faces from the sun.

From the Recueil Fossard, a scene depicting the clowns Arlecchino and Zanni Corneto, with the miser Pantalone.

Because the Commedia was improvisational, like some later Roman theater, it lent itself to political commentary. In attempting to appeal to the masses, it also tended toward the bawdy. This led European religious authorities to attempt to ban it in many places at many times, but never with lasting success. The Commedia‘s ultimate demise came from changing tastes rather than religious zealotry. But the masked characters survive in Venetian Carnival, where they remain popular even today.

The comic actor Giovanni Gabrielli (“Sivello”) holding a mask. Etching by Agostino Carracci, ca. 1599.

The Commedia character Harlequin, depicted by Claude Gillot (1673-1722).

Pulcinella mask, ca. 1700, made of leather moulded over a wooden form and used by an Italian Commedia dell’Arte troupe. Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.